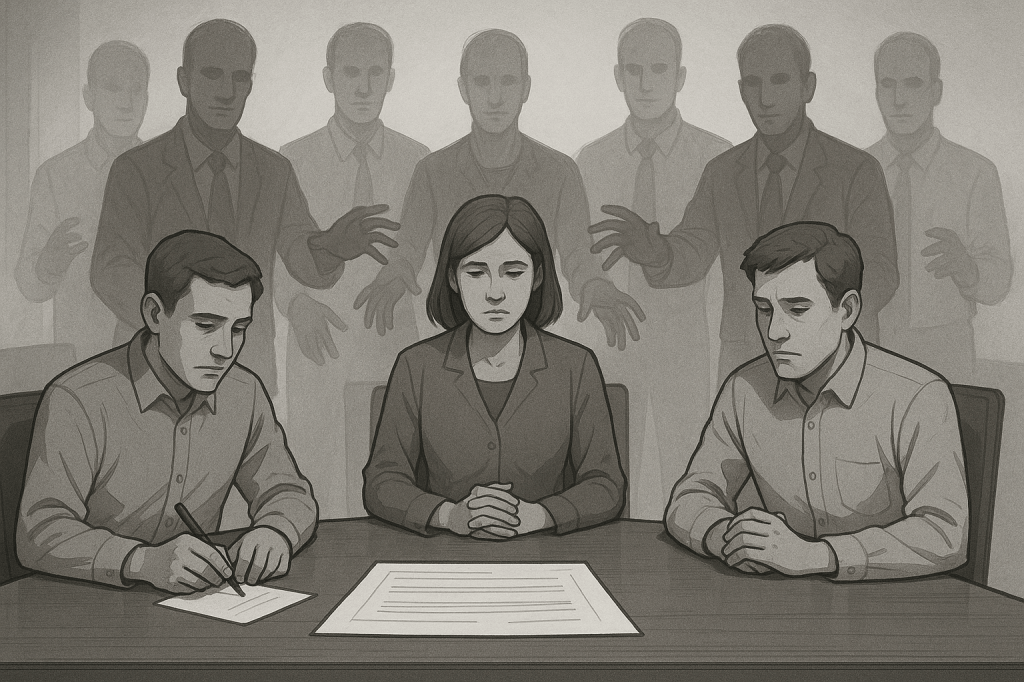

The product team sat in a small conference room, surrounded by six different managers. None of the managers belonged to the team. All of them insisted they were there to help. One wanted to influence development methodology. Another interpreted business signals. A third focused on retention issues. The room felt heavier than it should have. Every question triggered hesitation. Nobody knew whose mandate mattered. Nobody knew whether this help could be declined. Leadership had created these roles to support the team, yet the effect was the opposite. Authority had split into fragments. Expectations floated between people without settling anywhere. The architecture had begun to pull the organisation apart. Most of the people in the room felt the weight of it without having the words for it.

This is what I call organisational debt. Organisational debt is the accumulated weight of unclear mandates, improvised structures and role deviations that slowly misalign a company. It shows up when the formal architecture and the real work no longer match. It grows when leaders compensate instead of clarifying. It produces friction that people feel in their daily work without understanding why everything has become harder.

Although the term is sometimes used informally, there is now a growing body of research that describes similar phenomena. Some scholars define organisational debt as the residual friction left behind by outdated structures. Others describe it as the organisational counterpart to technical debt, created when short term decisions are never revisited. Where my definition differs slightly is in emphasis. Research often focuses on processes and formal governance. My concern is with the space between the people who carry the system. I believe the real debt accumulates when mandates are unclear, when roles drift away from shared meaning and when expectations remain unspoken. This kind of debt rarely appears in documentation. It appears in hesitation, in the inability to decide and in the sense that everything has become more difficult than it should be.

With this framing in place the examples become clearer. They are not isolated incidents or unfortunate dynamics. They are expressions of structural drift that many organisations experience without fully recognising it.

In one organisation the CEO and COO believed that the product managers in the infrastructure area were not doing enough market analysis. Instead of speaking to them about expectations, they rewrote the role. Market analysis was written into the job description and presented as decisive action. The intention was to strengthen the function. The effect was architectural damage. The company now had two incompatible definitions of a product manager. One matched the industry. One did not. From that moment forward every discussion about ownership required translation. Hiring slowed down because candidates struggled to understand what the company meant by the role. Mobility disappeared because one title contained two unrelated meanings. This is how role drift creates organisational debt. The problem is small at the moment of decision. The cost is paid later and by everyone.

A different kind of debt appears when mandates are unclear. The relationship between sales and development illustrates this better than theory. Sales works through opportunity. Development works through cadence. If leaders do not define how decisions are taken together, the two functions drift apart automatically. The drift then becomes personal. Sales begins to believe that development never delivers what customers need. Development begins to believe that sales changes its mind deliberately. The frustration grows until people begin to attach intent to the other side. In one company the story inside development was that sales tried to hijack the customer experience to rescue its quarterly goals. None of this was personality. It was the predictable outcome of two functions acting rationally inside an architecture that had never given them a shared mandate. This is how unclear ownership creates organisational debt. The conflict is structural long before it becomes emotional.

Organisational debt can also take the form of needless duplication. In an IoT accelerator programme we built a generic update solution intended for reuse by several teams. The idea was straightforward. Build once and benefit across the organisation. Senior leadership never made this expectation explicit and the absence of a clear mandate created confusion. Some engineers interpreted the generic solution as pressure to accept something that did not originate in their own group. They concentrated on corner cases. They questioned assumptions. One engineer eventually arrived proudly to demonstrate that he had built his own miniature version. He had spent precious time recreating functionality that already existed. The behaviour made perfect sense inside a structure that had never stated what belonged to whom. This is how unspoken expectations create organisational debt. The organisation pays for the same work twice because the architecture does not guide people toward shared assets.

Once you begin to recognise these patterns, they are difficult to unsee. They reveal themselves in the way meetings slip into clarification instead of decision. They reveal themselves in the way teams speak past each other even when they believe they are aligned. They reveal themselves in the quiet frustration that emerges when a question of ownership returns again and again because nobody can answer it with confidence. These are not cultural problems. They are architectural signals. The company is paying interest on decisions made long ago.

The path out of this debt does not begin with a reorganisation. That usually deepens the problem because it adds new layers on top of the drift. The first step is to bring expectations into the open. You ask what a team owns and what it does not. You ask how decisions are taken. You ask what success means in practice rather than in abstraction. The real architecture reveals itself when a leadership group attempts to answer these questions honestly. The room becomes quiet because people see how far their assumptions have drifted. That moment of silence is not failure. It is clarity. It is the point where the debt becomes visible.

From there the work becomes more direct. You remove ambiguity instead of compensating for it. You simplify instead of adding structure. You bring titles back to shared meaning. You anchor roles in expectations that do not require interpretation. When a team finally knows what belongs to them and what does not, their behaviour changes at once. Defensiveness falls away because the structure supports them rather than pulling them in competing directions.

I have seen this change organisations overnight. When I brought sales and development into a room during a period of complete hostility, I placed customer complaints on the table and asked them to decide together how to address them. Nobody spoke for half an hour. Eventually the silence broke and the hostility collapsed. They began to design solutions together because the problem had finally become shared. The architecture had been repaired at the simplest possible level. They understood their joint mandate. Behaviour followed structure, as it always does.

Organisational debt is not the result of weak culture or difficult people. It is the natural consequence of growth. The mistake is not the drift itself. The mistake is failing to maintain the architecture that holds the organisation together. When leaders understand this, they stop treating friction as a personal failing and begin to see it as a structural signal. They recognise the debt for what it is. Once they do, the path back to clarity becomes straightforward. They restore shared meaning. They remove the noise. The organisation begins to move again because the architecture finally fits the work.

scholarly note

Several strands of research address organisational debt, although the terminology varies. A review published in PLOS One describes it as the accumulation of outdated structures and processes that reduce an organisation’s ability to adapt. Researchers at the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon have written about organisational debt as the organisational counterpart to technical debt, created through short term decisions that are never revisited. Studies in organisational science emphasise that this debt is often invisible in formal documentation and becomes visible only when friction accumulates in daily work. These perspectives differ in detail but share a single observation. When structure drifts away from purpose, the cost is paid in slower decisions, misaligned teams and reduced adaptability. My own definition places particular weight on unclear mandates, improvised roles and the silent expectations that shape how people act long before any process is written down. This is where most organisations feel the debt first and understand it last.

#OrganizationalDebt #Leadership #OrganizationalDesign #ProductManagement #ScalingCompanies #BusinessTransformation #OrganizationalClarity #SystemsThinking #LeadershipDevelopment #StrategicExecution #TechLeadership #ChangeManagement #ExecutiveLeadership #OperationalExcellence #BusinessArchitecture #TeamAlignment #DecisionMaking #CrossFunctionalLeadership

Lämna en kommentar