Have you ever been to the gym?

If you take training seriously, the conversation always drifts the same way: how do I make this the best session ever, the one that changes everything?

Pro bodybuilder Jordan Peters once heard that question and simply smiled. “I don’t ever try to have my best session,” he said. “I build a year of work.”

He started from the end. For chest, he counted 52 weeks, 2 sessions a week, 104 chances to get stronger. “Where do I want to be in a year? What will my bench press be? And what do I need to do today to move toward that goal?”

He calculated backwards, and instead of chasing perfection in a single workout, he knew exactly what each session had to achieve for the long-term goal to make sense.

That idea changed the way I think about leadership. Most organisations still train like beginners at the gym. They try to win every session, every sprint, every quarter, and forget that strength is built over time. Leadership is no different. It is not about the best quarter ever; it is about building capability that lasts.

Three rhythms of time

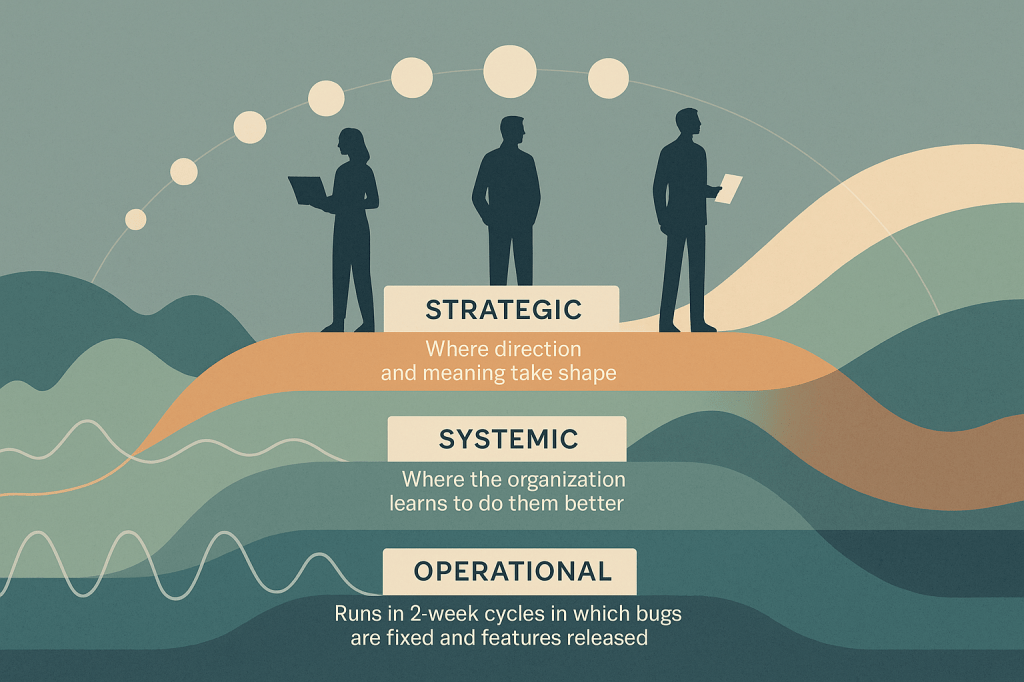

To lead well, you must live in several time scales at once: the operational, where things get done; the systemic, where the organisation learns to do them better; and the strategic, where direction and meaning take shape.

Operational life runs in 2-week cycles in which bugs are fixed, features released and customers answered, while strategic life stretches over years and asks where the market is heading, what the company should become and what identity it is trying to build.

Between those two lives the system level, the gearbox of the organisation, tunes and improves the rhythm of work and keeps the whole machine moving.

The gravity of what we know

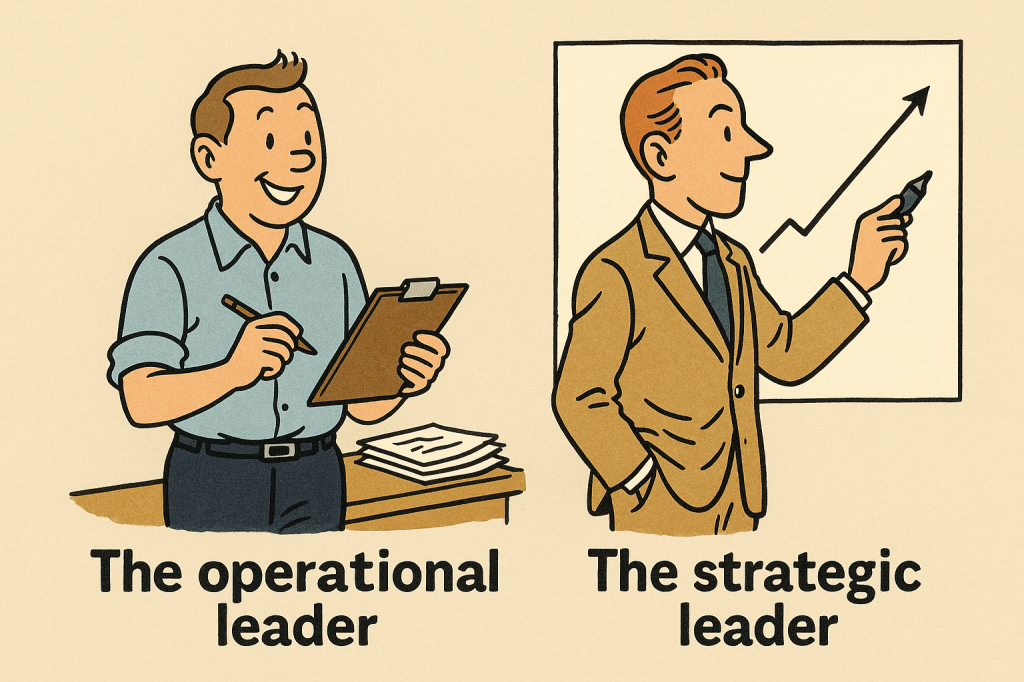

Most managers have worked their way up. They were good at what they did, then promoted, then promoted again. Their strength lies in the operational; they know how to make things happen, and there is a natural gravity that pulls them back to what they do best because it feels safe.

At the other end are the strategically trained. You can almost see the caricature: someone from a comfortable family, the right schools and the right networks. A leadership broiler, fluent in vision and positioning but with perfectly clean hands, able to draw the vector yet without a sense of the friction required to move something real.

Both rhythms on their own are incomplete. The operational leader gets trapped in activity, while the strategic one drifts into abstraction. Between them lies the system level, the organisation’s ability to learn. The best leaders move fluidly between these worlds; they know when to speed up, when to reflect and when to lift their gaze.

When the operational tries to fix the system

I have seen what happens when the operational side tries to fix the system with its own logic.

At Ubisoft I led several global agile teams, and we wanted to coordinate better, so we decided to bring in SAFe, the Scalable Agile Framework. It was a serious effort, well funded and full of capable people, but somewhere around 60% in we realised that something fundamental was breaking.

The system perspective began to collapse. SAFe became too expensive and too heavy, filled with roles that existed only to optimise the 2-week sprint cycle. The strategic view disappeared, and with it the space for learning.

A system cannot be managed with operational logic; it lives only in the dialogue between the immediate and the long term, growing through reflection, through feedback and through the small adjustments that make people smarter together.

I once saw the same pattern in a logistics company that tried to coordinate deliveries and production through a weekly steering committee. After 3 months the process charts were immaculate, but the trucks still waited at the gates. The real issue was that nobody owned the handover between scheduling and loading. When they gave that responsibility to a small cross-functional team, the backlog vanished in a week, and the lesson was obvious: systems fail in the spaces between people, not inside them.

What system work actually is

So what does the system level look like in practice? It is not another hierarchy or a new layer of management; it is the place where you improve the organisation’s ability to work. It is where handovers are aligned, recurring frictions resolved, learning made visible and habits of reflection built into everyday routines.

System work rarely announces itself. It appears in small moments, when 2 teams pause a meeting to trace how their work really flows between them, when a retrospective quietly turns into an actual change, or when a manager realises that the monthly meeting no longer produces decisions and reshapes it until it does. Most of the time nobody calls it transformation, but that is exactly what it is.

System work is seldom glamorous. It cuts across departments, challenges routines and sometimes threatens small empires, which is why it so often falls between the cracks and why it needs leaders who can stay patient when progress feels slow.

When this rhythm is alive, the organisation learns to adjust itself; when it weakens, the gearbox grinds and everything overheats.

When the strategic tries to fix the system

I have seen the opposite too, when the strategic side tries to fix the system from above. In one company, the leadership team began its transformation in the business plan. The intention was good: a new vision, new values and new goals for growth. The slides looked wonderful, but nobody had spoken with the developers, the support teams or the people who actually kept the company running.

The new initiatives floated above the organisation like balloons without strings. Teams quietly returned to their old routines, not out of resistance but because the plan was impossible to live in. It ignored the dependencies and rhythms that kept the place functioning.

When the operational side tries to fix the system, it drowns in activity, and when the strategic side tries, it drifts into abstraction. The system level cannot be installed from above; it has to grow from genuine conversation between the two.

Learning to change gears

Maturity in leadership is the ability to shift between these three rhythms. It begins with awareness: look at your calendar and ask how much of your time belongs to the next 2 weeks, how much to the next 6 months and how much to the next 2 years.

Create spaces that match each rhythm, such as weekly operational check-ins, quarterly system reviews and half-yearly strategic discussions, and train your perception so that each time a problem appears you ask yourself which rhythm it belongs to. Are you fixing a symptom, or improving the system that produced it?

On Monday, start small. Choose one recurring friction point such as a handover, a decision delay or a misaligned goal, and treat it as a system problem rather than a performance issue. Bring the people involved into one room, map what happens and agree on a small adjustment that could make it smoother, then track the effect for a month. That is system work in its simplest form.

I still catch myself falling into the 2-week trap, as every leader does, but these days I try to listen for the rhythm before I move. Leadership is not about running faster; it is about knowing when to change gear and about building the kind of discipline that Jordan Peters described, where each repetition is part of something larger.

I think of him often. No drama, no miracle sessions, just a plan, a rhythm and a year of work. Leadership is not so different. It is about keeping the rhythm steady enough that everyone else can grow stronger within it.

Further reading

If this way of thinking resonates with you, these works have shaped how I see leadership and learning.

The leadership pipeline by Charan, Drotter and Noel

A clear map of how leadership responsibilities evolve as you move up the organisation, and why the habits that made you successful at one level can hold you back at the next.

The fifth discipline by Peter Senge

The classic book on learning organisations that shows how systems thinking turns mistakes into insight instead of blame.

Diagnosing the system for organisations by Stafford Beer

Dense but brilliant, it explains how complex systems stay alive and why feedback, not control, is the real currency of leadership.

Team topologies by Skelton and Pais

A modern and highly practical guide to structuring teams for flow, communication and learning.

Theory U by Otto Scharmer

A reflective book on awareness and transformation that shows how leaders can shift from reacting to sensing and co-creating.

Let’s talk

I work with leadership teams and mid-level managers to build this rhythm inside their organisations, reconnecting operational work, systemic learning and strategic intent.

If you would like to explore how it could look in your context, you can book a short conversation at calendly.com/mansen66/jorn-1on1

or read more at jorngreen.online.

Lämna en kommentar