Game development is a strange kind of creative work. It’s not painting a picture. It’s not coding an app. It’s building an entire little world, one that moves and reacts, one that has to hold together logically while still being fun. And the process to get there—what we call the pipeline—is rarely as clean as the charts make it look.

You start with an idea. You build a world. You create assets, systems, behaviour, interfaces. You test, polish, break, fix, test again. The work is intense, especially in small or mid-sized teams where everyone wears more than one hat. And somewhere along the way, the energy dips. Something gets blocked. A character isn’t coming alive. The environments feel dead. Or you’re stuck waiting for a round of assets that just aren’t ready yet.

That’s when I started bringing in AI—not because I was chasing a trend, but because we didn’t have time to stay stuck.

I want to share five tools that have actually helped. Not theoretically. Not in a sales pitch. In production. Each one had its quirks, its limitations—but also real value. And if you’re curious, I’ve included links to all of them.

We were preparing a vertical slice and trying to get a hallway scene to feel like part of the world. The layout was in place, the lighting was roughed in, but it felt empty. The art team was busy with hero assets and didn’t have time to fill in shelves, furniture, junk—the stuff that gives a space its life. I decided to test Scenario to see if we could generate something passable.

The first few attempts were a mess. Wrong perspective, weird colours, items that made no sense. But once I trained a model using some of our existing art, the output started to come together. Suddenly I had a bunch of small props that actually fit. I didn’t tell anyone at first—I just dropped them into the scene. And when we reviewed the level later that week, nobody flagged the assets. They just commented that it felt “more complete.” That was all I needed.

Scenario is an AI image generation tool you can train on your own art style. It’s web-based, and while the interface isn’t the most intuitive, the results are surprisingly consistent once you’ve dialled in the prompts. You can generate props, concepts, even characters—and for teams who need quick visual iterations, it can really save time. But don’t expect miracles. You’ll still need someone with a good eye to pick the results that work.

Writing NPC dialogue is one of those tasks that looks easy until you’re knee-deep in it. I had a supporting character—a seasoned soldier, now reluctantly helping the player. He needed to sound credible. Not wise, not wooden. Just… real. I tried a few variations of his lines, but nothing felt quite right.

I decided to give Inworld a go. I gave it the character’s backstory, set his mood and personality traits, and ran a few test conversations. The first thing that struck me was how naturally he answered. Sometimes short. Sometimes sarcastic. Sometimes refusing to help outright. Not every line was usable, but the tone was there. It felt like a person.

What Inworld does is simulate character behaviour. Not just dialogue trees, but reactive, evolving responses. It’s not a writer. It won’t structure your story arcs. But it’s incredibly useful when you’re trying to find a character’s voice—or when you want to see how a player might bounce off different personalities. It also integrates with both Unity and Unreal, which makes testing in context easier.

What you give it matters. Garbage in, garbage out. But give it a strong foundation, and it gives you something to build on.

We’d been stuck in greybox limbo for a while. The level design was solid, but everything felt cold and dead. People kept saying, “it’s fine, I can imagine it,” but that wasn’t good enough. You don’t feel pacing in a greybox. You don’t feel story beats.

I’d heard about Promethean AI, so I gave it a shot. The setup was a bit technical—this isn’t a drag-and-drop tool—but once we had it running inside Unreal, I could literally speak to it. “Make this corridor look abandoned,” I said. “Add debris on the right side.” It listened. It filled in the scene with enough visual information to break through the feedback block.

Promethean doesn’t replace your level artists. But it speeds up the part of the process where you’re trying to make decisions. It helps you go from empty shell to lived-in space, so the team can react to something real. And when time is tight, that makes all the difference.

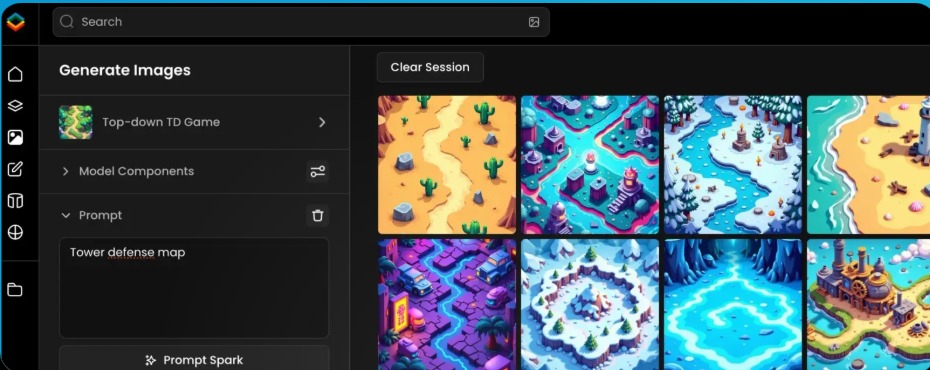

We were short on time, and the UI team was swamped. We needed quick visuals for item icons—potions, runes, ability upgrades. Nothing fancy, just something stylized and functional. Normally, I’d ask someone to make sketches or repurpose old assets. Instead, I logged into Leonardo.

It’s probably the most straightforward of the tools I’ve used. You give it a prompt, maybe a style reference, and it generates a batch of images. It’s designed for game assets—icons, environments, concepts—and works surprisingly well out of the box.

Some of the outputs were off. A few were weird. But a few were spot-on, and that was enough. We used them directly in the UI for internal testing. Later, we swapped in final art, but by then the designers already knew what worked.

Leonardo is ideal when you need “good enough” fast. It’s not consistent across multiple generations, so don’t expect to build a whole game’s worth of art with it. But when you need visual placeholders that look good enough to get buy-in or test UI flow—it’s solid.

QA is always where time gets squeezed. Everyone wants to test, but nobody wants to wait for it. And players find problems you never imagined. That’s where Layer came in.

We integrated it into a test build and let it run overnight. The AI agents moved through the level, trying weird things—stacking objects, jumping into corners, opening menus mid-combat. In the morning, we had a report: broken states, weird collision bugs, a few gifs of truly cursed player behaviour.

Was it perfect? No. We still needed human QA. But Layer caught things early, and more importantly, it let us test changes fast. We could do a pass, fix bugs, run again. That rhythm is hard to find with manual testing alone.

Setting it up wasn’t trivial. The behaviour modeling took some time to tune. But once working, it added real value—and the team started trusting the results.

AI didn’t replace anyone on the team. It didn’t cut headcount, and it didn’t finish the work for us. What it did was break bottlenecks. It kept the flow going. And in game development, momentum is everything.

These tools—Scenario, Inworld, Promethean, Leonardo, and Layer—aren’t magic. But they’re real. They’ve made production smoother, faster, and in a few cases, even a bit more fun.

I’m not writing this to evangelize AI. I’m writing it because I’ve used these tools, and they’ve helped. If you’re building games, especially under pressure, they might help you too.

Lämna en kommentar